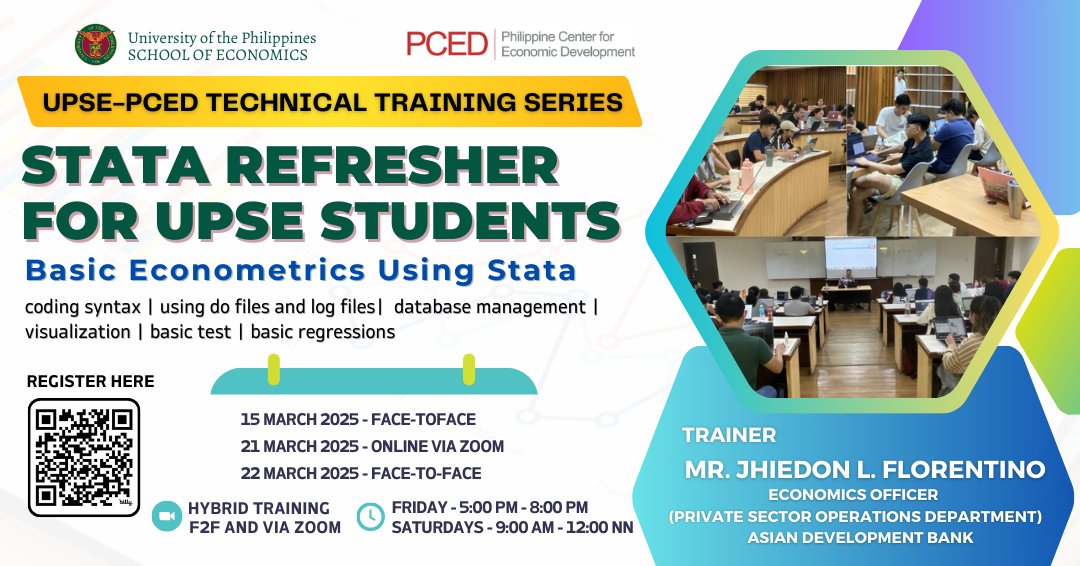

This is a hybrid training; Participants are expected to attend 𝙖𝙡𝙡 𝙨𝙚𝙨𝙨𝙞𝙤𝙣𝙨. Priority will be given to Students in advanced economics and econometrics courses and thesis writers (Econ 199, Econ 138, Econ 233, Econ 298, DE 253 & DE 292). Limited slots only. Other students and non-UPSE students may be accommodated depending on the available slots.