Core

Business World, 18 June 2014

The unemployment rate dipped to 7% in April from 7.5% in April last year. The number of employed people rose by 1.6 million, according to the 2014 April Labor Force Survey results. Is the employment picture truly improving? Has the Aquino administration finally found the winning formula for fixing the Philippines’ joblessness problem? The answer is “no” to both questions.

Here are some inconvenient truths about unemployment in the Philippines.

First, while 1.6 million jobs were created from April 2013 to April 2014, about one in five new workers toiled without pay in his own family operated farm or business. This category of employed but unpaid workers increased from 4,034,199 in April last year to 4,330,480 in April this year, or by 296,281 workers.

In short, since the total work force is about 42.9 million, one of 10 “employed” workers was not even paid.

Second, some 7.03 million workers — or close to two of every 10 “employed” workers — are underemployed. These are workers who want paying jobs, or want additional hours of work in their present job, or want additional work, or want a new job with longer hours.

Third, the number of visibly underemployed workers is rising. These are underemployed workers who toil for less than 40 hours in a week. In April this year, they accounted for 61.4%, significantly higher than in April last year (53.7%). In terms of warm bodies, there were 4,288,300 visibly underemployed workers in April this year, compared to 3,810,552 such workers in April last year, or an increase of 477,748 workers year-on-year.

Fourth, the deterioration in the quality of jobs is comprehensive as it is observed in all sectors. In agriculture, which accounts for 30.7% of the labor force, the number of workers who worked for less than 40 hours in a week increased from 64.2% in April last year to 67.7% in April this year. By contrast, those who worked for 40 hours and more in a week dropped from 34.1% to 30.5%. During the same period, the average number of hours worked fell from 41.9 hours to 40.3 hours.

In industry, which accounts for 16.4% of the labor force, the number of those who worked for less than 40 hours in a week increased from 19.4% to 25.8%. By contrast, those who worked for 40 hours and more declined from 79.7% to 72.6%. At the same time, during the same period, the average number of hours worked in a week shrunk from 44.3 hours to 42.4 hours.

In services, which accounts for 52.8% of total labor force, the number of those who worked for less than 40 hours in a week shot up to 25.9% from 21.6%. In contrast, those who worked for 40 and more hours declined from 47.1% to 45.5%. During the same period, year-on-year, the average number of hours worked in a week shrank from 47.1 hours to 45.5 hours.

The inescapable conclusion is harsh but true: workers across all sectors are working fewer hours as full-time jobs are being replaced by part-time jobs. That’s retrogression, not progress.

The April 2014 report gives an illusion that the Aquino administration is doing a great job in fixing the country’s unemployment problem. And there are three qualifying statements that would support the proposition that the employment picture as shown in the survey results is illusory.

First, the report does not consider overseas Filipino workers as part of the working population. Most migrant workers are giving up the comfort of home and family because they can’t find decent and rewarding jobs at home. By ignoring this rising cadre of the Filipino diaspora, the size of the work force is artificially reduced; hence the size of the unemployed work force is likewise understated.

This treatment of overseas Filipino workers could lead to perverse public policy prescription — which is to push Filipinos to work abroad so that the labor force will shrink and unemployment, other things being constant, will fall.

Second, the survey results exclude employment and unemployment numbers in Leyte province on the pretext that, as an aftermath of super typhoon Yolanda, it is virtually impossible to get an accurate picture of Leyte’s job market situation.

Let’s do the math. Before Yolanda, the province of Leyte has a labor force of about 1.3 million workers. Assuming that two in 10 workers in Leyte province are unemployed — a reasonable assumption since the agricultural sector has yet to recover and private business activities have yet to reach pre-calamity levels — then the implied nationwide unemployment rate would be approximately 7.4% and not 7%. Both the adjusted and official unemployment numbers are much higher than the official government target unemployment rate of 6.7% in 2014.

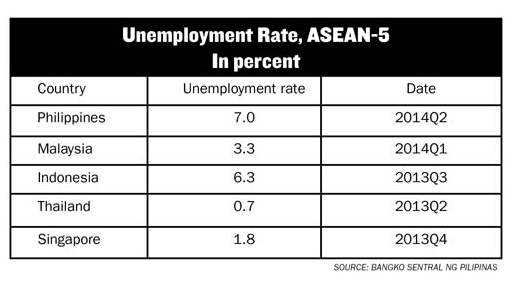

Third, even the propped up 7% rate of unemployment is much higher than unemployment rates in the ASEAN-5 region. Put differently, the Philippines’ 7% unemployment rate is markedly higher than the other four ASEAN countries (see table).

In sum, the claim that the Philippine employment situation has improved, based on the government’s survey results, has no leg to stand on. Workers who worked less than 40 hours in a week shoot up from 12.8 million in April last year to 15 million in April this year, or an increase of 2.2 million; this more than offsets the 1.6 million jobs created during the same period.

In sum, the claim that the Philippine employment situation has improved, based on the government’s survey results, has no leg to stand on. Workers who worked less than 40 hours in a week shoot up from 12.8 million in April last year to 15 million in April this year, or an increase of 2.2 million; this more than offsets the 1.6 million jobs created during the same period.

Fixing the Philippines’ joblessness problem remains a herculean task. More than 1.2 million new workers join the labor force every year, and about half of the jobs that exist are of poor quality. The real risk is that in a slowing or flattish economy, this pitiful state of joblessness could easily get worse before it gets better.